Disha P Bharadwaj, a practioner of Carnatic music for almost 5 years ,under the guidance of Dr. Chinmaya M Rao.

Disha loves to explore different genre of music such as light music, Bollywood and Hollywood. She is also a YouTuber.

Dr. Chinmaya M Rao, is the founder of Kannada Times, NGO/Eye Dreams Promotions, being Disha’s music Guru recommended Disha to a film Director who was looking for an upcoming child singer for the Tamil dubbed movie.

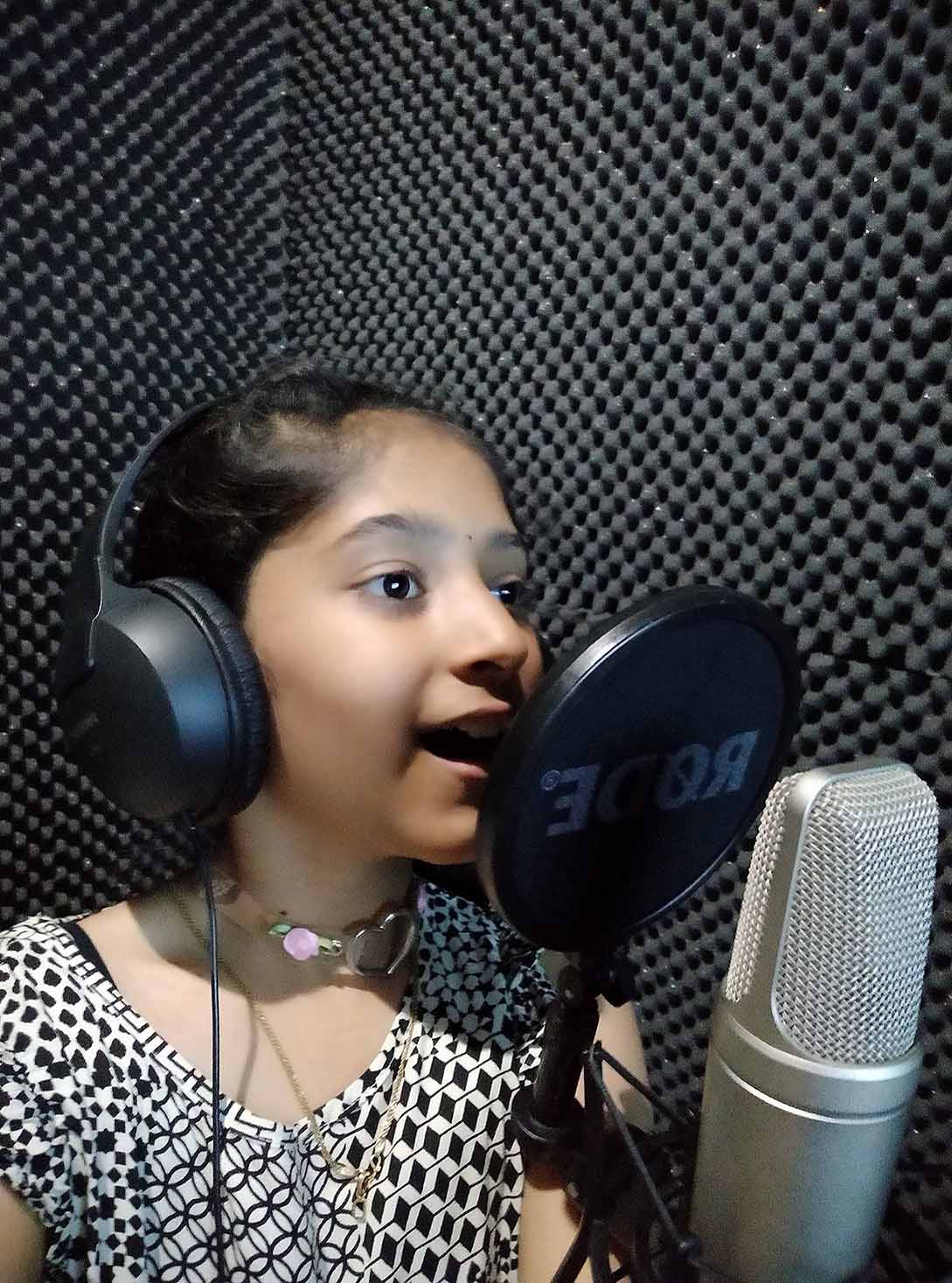

On The Auspicious Day Of Dasara, She Was Called For Playback Singing For Pasanga2 , A Tamil To Kannada Dubbing Movie, in a studio in Gandhinagar, Bengaluru.

Disha was overwhelmed with the opportunity and said ” I’m in gratitude with my Guru Dr Chinmaya M Rao for believing in me and giving me the opportunity and also a big thanks to Director Mr. Anil.